It is beautiful.

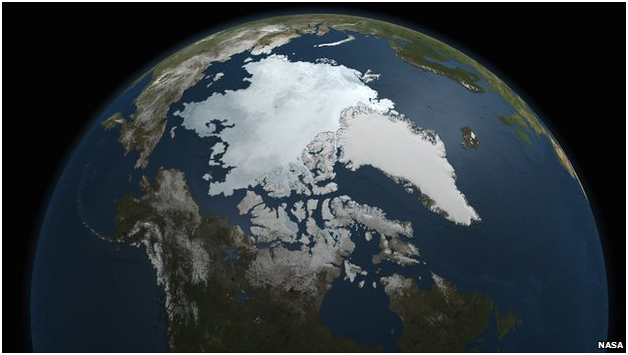

Ten days ago, a NASA satellite took this image, a reminder that we are blessed to live on a planet rich with water and green with abundant life. Seen from 440 miles above the Arctic Circle, the earth seems peaceful, perfect and unchanging.

Yet, there are other, hidden stories in this image—important details that can escape notice at this distance, unless you know what to look for.

There is, for instance, the ice that is not there. When this image was taken on September 10, 2010, the Arctic sea ice was near its annual minimum—the point each year at which the area covered by sea ice is at its lowest (it has dropped a little further in recent days). This year, the sea ice fell to its third lowest level ever, surpassed only by the record lows in 2007 and, by a hair’s breadth, 2008. The ice retreated so far that for several weeks this summer, the fabled Northwest Passage was no longer a fable. As this photo documents, the Northwest Passage—no more than a sailors’ myth until two years ago—opened for nearly a month this year, making it possible to sail from Atlantic to Pacific across the Arctic. In fact, with a fast enough ship you could have made the return journey by the Northeast Passage over Russia, and circumnavigated the entire Arctic Ocean in a single season. For the first time in human history.

Is this a boon to global navigation? Perhaps. Is it a clarion call for a changing planet? Beyond a doubt.

Consider the people you don’t see in this image. Too small to make out from such a great height, but still there. And profoundly dependent on the ice to maintain their livelihoods, their communities, and their cultures—Inuit, Yupik, Gwich’in, Saami. Arctic peoples depend on the sea ice to travel between mainland and islands, for access to traditional resources, like walrus, that are themselves threatened by the vanishing ice, and for protection from increasingly severe storms that are eroding coastlines, homes, schools, and entire villages.

Nor does the satellite see the billions of tons of greenhouse gases enshrouding the atmosphere, threatening both the Arctic and those who live there. That threat, like the pollutants themselves, reaches people on every corner of the planet: the people of Bolivia and the Himalaya, whose water resources are threatened by melting glaciers, people of the Atlantic islands, where larger and more intense hurricanes are becoming more frequent, those of the Pacific and Indian Oceans, where entire islands are imperiled by relentlessly rising seas, and the nearly one billion people of Africa, most vulnerable of all continents, who face increased flooding, drought, hunger and insecurity as a consequence of global climate change. (Click here for CIEL case studies on global warming impacts to communities on four continents.)

This is the challenge of global warming—the challenge of confronting an invisible pollutant, changing the world in ways that are profound but not always obvious, in places that too often escape our notice. It is a challenge whose effects are tolled not only in lost species and lost resources, but in human lives, human livelihoods and human rights. And whose costs are borne disproportionately by people far removed from the factories, board rooms and seats of power where the threats originate. Finally, with both the causes and the effects of global warming spanning entire continents, it is a challenge no one country can face alone.

It is for just such challenges that CIEL was created, and why it exists today. From the development of civil rights to the dawn of the environmental movement, history has proven time and again the power of law as an instrument of change and a vehicle for justice. At its best, law is transformative—according equal stature to parties of vastly unequal resources, translating abstract statistics and hidden stories into the living, resolute voices of real human beings, demanding to be heard not out of pity, but as of right, and setting precedents that benefit not only themselves but others like them.

Since its founding in 1989, CIEL has worked to translate this transformative approach to law from the domestic landscape where it was born to the global landscape of international environmental law—with frequent and often profound success.

CIEL’s use of international law to protect the environment, promote human health and ensure a just and sustainable society remains as innovative and vital today as it was twenty years ago. As does CIEL’s commitment to continually building new international law and new international lawyers to use it. It was this commitment that brought me to CIEL as an intern in 1996, and that inspires me today as I return to lead the organization into its third decade.

The challenges of this next decade are already with us. As I finish this on Monday, September 20th, my first day as CIEL’s new President, a new NASA image is on my mind. It is the image of Hurricane Igor–one of a remarkable four hurricanes active in the last week, and at nearly 700 miles in diameter, one of the largest Atlantic hurricanes ever recorded–as it bore down on the island and the people of Bermuda. Law alone cannot solve the challenge of climate change, but there is no solution without law. I am humbled to join CIEL in the ongoing quest for that solution.

Originally posted on September 20, 2010.