Photo via #CongaNoVa

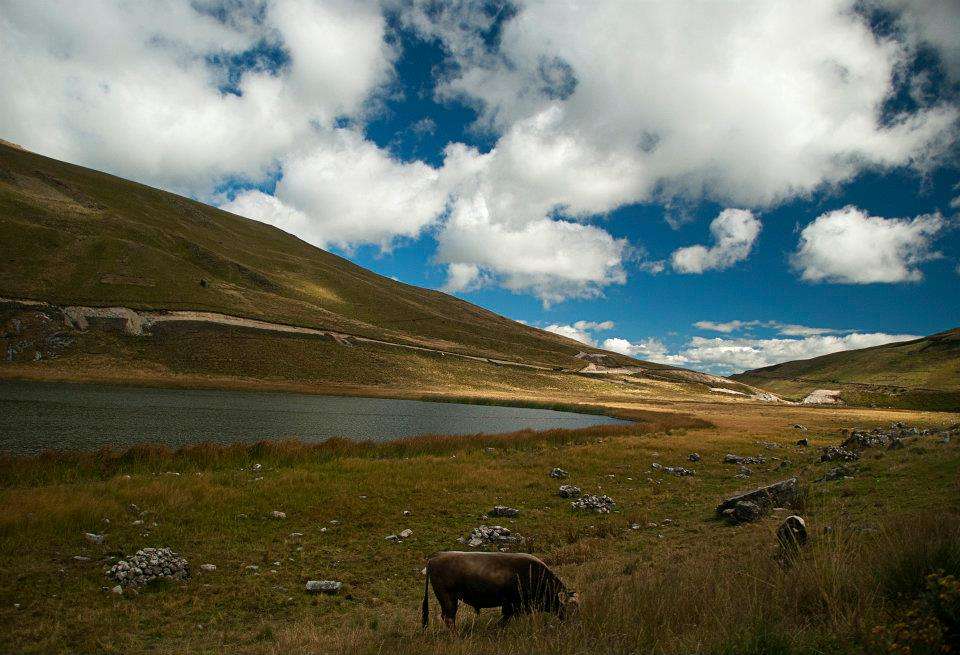

Every fifteen days in the Celendín province of Peru, hundreds of community members trek through the Andes Mountains to participate in a peaceful march to pristine high altitude lakes. Although the backdrop of their activity could be picturesque vacation location, for this group of vigilant protestors, the site has been marred with bloodshed, persecution, and the threat of destruction by US-based Newmont Mining Corporations’s Conga mine project.

A few weeks ago, Milton Sánchez Cubas, a member of this community and outspoken leader for the protection of the Celendín area from the Conga mining project traveled to Washington DC to release a new report critical of the project, and to meet with representatives from the World Bank and the US government to advocate in defense of the community’s life and territory. Accompanied by the Columbia Law School Human Rights Clinic, Milton stopped by the CIEL office to discuss the human rights violations that have occurred surrounding the Conga project and how his community has persevered against all odds.

Celendín is a community located in Cajamarca Peru, and its Jalca ecosystem, which consists of high altitude lakes and wetlands, is vital for its ability to trap fresh water and distribute it to communities in the region. The area serves as the source for over 600 springs, 100 water sources for human consumption, and 18 irrigation canals that extend into three unique provinces.

Photo via #CongaNoVa

The Conga mining project, a joint venture between Newmont, Peruvian company Minas Buenaventura, and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) – the private lending arm of the World Bank, is projected to fundamentally transform this area. Milton explained how the project would unearth some 150,000 tons of rock each day, create a 300-hectare dam of liquid tailings, and potentially eliminate the ecosystem services (including food and water) provided by this region. Similar to the nearby Yanacocha mine, once the largest gold mine in South America, the Conga project is expected to have serious environmental and human rights impacts including: serious contamination of water supplies, costs for water treatment, dramatic reduction in biodiversity in the area, infringement upon cultural traditions, construction of hydroelectric dams (to support the energy needs of the mines), and the release of heavy metal content into the environment, which is linked to serious health impacts, including death, to livestock and people.

Although the courageous citizens of Cajamarca have been able to indefinitely halt the construction of the Conga project through their unyielding protests and legal actions, they have faced serious challenges and human rights violations. First, the state has militarized many of the areas where protests have been held. Further, in November 2011 and July 2012, violent repression of protests resulted in over 150 injuries and 5 deaths. The violence was accompanied with over 300 criminal complaints filed against protestors and complicit media stigmatization of protests, labeling activists as drug dealers and terrorists.

Photo via #CongaNoVa

The Celendín case demonstrates a dangerous trend in Peru: the systematic prioritization of “development” via disastrous mining projects over protecting human rights. What’s more, this project is just one of a suite of projects planned for this area. But the communities in Celendín remain committed in their defense of their rights and environment, and the bimonthly occupation of the lakes are just one of the ways in which the community continues to assert its rights and remain vigilant to the threat of Conga Mining Project.

Sanchez Cubas’ visit to Washington amplifies the community’s voice in an international arena, allowing it to confront the World Bank as an investor, form alliances with other organizations fighting for human rights against mining corporations, and challenge the extractive development model worldwide.

For more information visit:

For the broader context of mining in Peru: What Does the Brutal Crackdown on Protestors in Peru Have to Do with the World Bank Meetings in Lima Next Week?

Originally posted October 30, 2015