By Amanda Kistler, Guatemala Project Campaigner

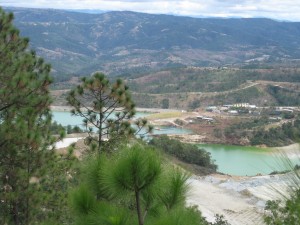

As the muted colors of the Guatemalan altiplano blurred by the tinted windows of the van, something in the valley caught my eye: an enormous, nearly glowing chartreuse-colored body of water. Closer inspection revealed this unnatural color emanated from the residual waters in the tailings pond of Goldcorp Inc.’s Marlin Mine in San Marcos, Guatemala.

Despite having worked in Guatemala for two years, I had never seen the Marlin mine until now. During my years living in rural Guatemalan communities, I had begun to appreciate the deeply interwoven relationship between indigenous Mayan campesinos and their lands. In Guatemala, land is life. Period.

And so in spite of significant obstacles, Guatemalan communities are organizing to defend their right to land, to life. Meanwhile, rumors circulate in every corner of the country warning of impending mining projects and other large-scale “development” projects that would force people off their lands or render their lands unusable. If the past is any indicator, community members have every reason to take these rumors seriously.

Guatemala is a potent mix of natural resource potential, historic popular disempowerment and near total impunity. This combination makes Guatemala a dangerous (yet attractive) setting for large-scale extractive industries. The Guatemalan government welcomes the investment, companies pay only 1% in royalties and enjoy little government oversight, and local communities suffer the consequences.

For Francisco Salomón Bámaca Mejía and his neighbors in San José Ixcaniche, these consequences were never discussed before the mine began construction. Salomón remembers when the prospectors for Goldcorp’s Marlin mine first came to his community. “They never said they were going to exploit the land,” he recalled. “They said they were collecting orchids and were interested in bettering the plants.” He said it wasn’t until the company had begun digging ditches that the nearby communities learned the company sought gold and silver, not orchids. It’s unclear what local authorities knew about the project.

Today, community members claim they still do not know of the company’s plans. “We learn they are blasting tunnels nearby when our houses begin cracking,” recounted one man at a community meeting in November 2010.

At the Marlin mine, Vancouver-based Goldcorp uses a cyanide-leaching process to separate metal from ore, yet insists that the mine has no negative impact on the environment, and that the company has respected national laws. However, studies by E-Tech International, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) and the University of Ghent show elevated levels of heavy metals, like arsenic and lead, in the blood and urine samples of people living closest to the mine. “Doctors from PHR came and took samples of my blood,” Salomón told us. “And they told me I am contaminated. There is metal in my blood.” From his front porch I could see the broken earth around the mine, its exposed dirt bleeding like a wound onto the green landscape.

So far in Guatemala, Goldcorp’s Marlin Mine is unique. It is the largest, most wildly profitable and most high profile mine in the country. However, it portends a dangerous precedent for indigenous communities; there are more than 400 mining licenses issued in Guatemala. Marlin is a scary precedent.

On the other side of the country from Marlin, a gathering of women affected by a Canadian-owned HudBay nickel mine in El Estor met with women affected by the Marlin project in San Marcos. Sitting around a circle of brightly colored candles, the women shared their experiences about the unique challenges they face as women affected by mining projects. The air was stifling, and a steady drone of cicadas muted other extraneous noise. Through the buzz, one woman began speaking. Her voice was low at first and halting, but quickly gathered vehemence as she detailed the ways mining has destroyed her community. By the end she was nearly shaking, “We are alone down here. We are working; we are sacrificing; we live with this injustice everyday. In our ways we fight. But the international community has the responsibility to fight with us. We must all fight together, all of us in our own way. Those in the North have the responsibility to act or you become complicit in the abuses.”

Her words were not an accusation. Instead, they are part of an increasingly vocal articulation of the need for more globally coordinated strategies to defend the rights of communities as they confront the interests of large-scale extractive industries.

* * * *

CIEL works with impacted communities to ensure Guatemala respects its international obligations through various international and institutional grievance mechanisms. Through its work in the Coalition Against Unjust Mining in Guatemala – CAMIGUA, CIEL implements a variety of strategies to hold Goldcorp and both the Guatemalan and Canadian governments accountable.

Originally posted on February 25, 2011.